Investment Fundamentals: Build Wealth in South Africa

Learn investment fundamentals using familiar concepts like stokvels. Understand shares, returns, and opportunity cost in simple terms. Start building wealth in 2026

MONEY BASICSSOUTH AFRICA GUIDE

1/5/20269 min read

Long before formal investment platforms existed, our communities were pooling resources, managing risk collectively, and planning for the long term. If Stokvels have taught us the discipline, this article is about giving that discipline a better structure to grow real wealth in 2026.

1. What Is a Company? (The Group Effort)

Before we talk about shares, we need to redefine the word "Company."

A company is simply a group of people who pool their resources—money, skills, or time—to work towards a common goal for a long-term benefit.

When you think about it this way, a Stokvel is a company. You have members (shareholders), a goal (a payout or grocery run), and pooled resources (monthly contributions). A formal company like Vodacom or Shoprite is just a Stokvel on a massive, global scale.

Once you realize this, the stock market stops being a "high-rise building" mystery and starts looking like a familiar tool.

2. What Is a Share? (Stock = Share)

Whenever people split money, food, or responsibilities, each person receives a portion. That portion is a share.

In the investment world, a share is your unit of ownership in a business. When you buy a share, you are an owner. Whether you own one share or one million, you are an equal participant in that company's success.

Here's where it gets interesting: In the investing world, a share is also called a stock. The two words mean exactly the same thing. When someone says "I own stocks," they mean "I own shares." When they say "I bought shares in Shoprite," they mean "I bought stock in Shoprite."

So from here on, when you hear "stock market" or "stock exchange," just remember: we're talking about shares—pieces of ownership in companies.

3. Going Public: The Initial Public Offering (IPO)

Now, not all companies have shares that you and I can buy. Most businesses start as private companies—owned by the founders, their families, or a small group of investors.

But when a company grows large enough and wants to raise more money to expand, it can choose to go public. This is where the magic happens.

What Is an IPO?

An Initial Public Offering (IPO) is when a private company offers its shares to the public for the very first time. Think of it like a Stokvel opening its membership to anyone in the community, not just the original ten friends who started it.

The IPO Process: How It Works

Let me walk you through this step by step, keeping it simple:

Step 1: The Company Decides to Go Public

The owners sit down and say, "We need more money to grow. Let's sell part of our company to the public."

Step 2: They Hire Advisors

The company hires investment banks and financial advisors (think of them as the "IPO planners") to help manage the process. These experts guide everything from pricing to legal requirements.

Step 3: Determining Authorised Shares

The company decides how many shares to create. Let's say Shoprite decides to create 100 million shares. These are called authorised shares—the total number of shares the company is allowed to issue.

But here's the key: they don't have to sell all 100 million at once. They might only sell 30 million shares to the public initially. The remaining 70 million shares stay with the original owners (founders, early investors).

The 30 million shares offered to the public are called shares in issue or outstanding shares—these are the ones actively being bought and sold.

Step 4: Setting the Initial Price (Valuation)

This is where things get technical, but I'll keep it simple.

The company and its advisors need to answer: "What is one share worth?"

To figure this out, they:

Look at the company's profits, assets, and growth potential

Compare with similar companies already on the stock exchange

Estimate what investors would be willing to pay

Consider market conditions (is the economy strong? Are people eager to invest?)

Let's say they value the entire company at R10 billion. If they're creating 100 million shares:

Each share is worth: R10 billion ÷ 100 million = R100 per share

That R100 becomes the Initial Listing Price—the price at which shares are first sold to the public during the IPO.

Step 5: Marketing the IPO (The Roadshow)

Before the big day, the company goes on a "roadshow." Company executives meet with big investors (pension funds, investment firms) to pitch why they should buy shares. Think of this like a Stokvel treasurer convincing new members why they should join.

Step 6: The IPO Day

On IPO day, the 30 million shares are sold to investors at R100 each. The company raises:

30 million shares × R100 = R3 billion

This money goes directly to the company to fund expansion, pay debts, or invest in new projects.

Step 7: Listing on the Stock Exchange

Once the shares are sold, the company is officially listed on the stock exchange. In South Africa, this means it's now trading on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE).

From this moment forward, those 30 million shares can be bought and sold by anyone through the stock exchange.

A Stokvel Analogy

Think of your 10-member Stokvel deciding to expand. You create 100 membership positions (authorised shares), but only offer 30 to new members (shares in issue). The original 10 members keep 70 positions for themselves.

You decide each position is worth R20,000 based on your Stokvel's track record and savings pool. That's your "IPO price." Once the 30 new members join and pay R20,000 each, your Stokvel has raised R600,000. Now those 30 memberships can be traded among people in the community—that's your "stock exchange."

4. The Stock Exchange: Where Shares Get Traded

The term gives it away: this is where stocks (shares) get exchanged—changing hands, being bought and sold.

This is commonly referred to as the market. Think about the normal market you know: sellers come to sell their goods, and buyers are there to buy if they see what they like or need.

Why Is This Market Different?

Unlike other markets where you can have different markets in different locations or towns, the stock exchange is highly regulated. And this makes sense—in this market, there is no thrifting or bargaining over tomatoes. We are buying and selling ownership in companies.

Everything is tracked, recorded, and monitored to prevent fraud and protect investors.

South Africa's Stock Exchange: The JSE

In South Africa, this market is called the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE).

Founded in 1887, the JSE is where companies like:

Shoprite

Vodacom

Capitec Bank

Naspers

Anglo American

...list their shares for the public to buy and sell.

When you hear someone say "the market was up today" or "shares fell on the JSE," they're talking about the collective movement of share prices on the stock exchange.

5. Brokerages: Your Gateway to the Market

Now here's an important point: you can't just walk into the JSE and start buying shares.

This is not thrifting where you walk into a market, browse, and hand over cash. Share trading is formal, regulated, and requires intermediaries.

What Are Brokerages?

The companies or professionals you go through to buy and sell shares on the JSE are called:

Stock Brokers

Brokers

Brokerage Firms

Think of them as the gatekeepers or middlemen between you and the stock exchange.

Examples of South African Brokerages:

EasyEquities (beginner-friendly, low minimums)

Sygnia (low-cost, simple)

Standard Bank Online Share Trading

Investec

Old Mutual Wealth

These platforms allow you to:

Open an investment account

Deposit money

Buy shares listed on the JSE

Sell shares when you want

Track your portfolio

Why Do We Need Brokers?

Because the JSE has strict rules about who can trade directly on the exchange. Brokers are licensed, trained, and have the technology to execute trades instantly while ensuring everything complies with financial regulations.

In exchange for this service, brokers charge fees—usually a small percentage of each transaction or a monthly platform fee.

A Stokvel Analogy

Imagine your Stokvel is so successful that it creates a formal "Stokvel Exchange" where memberships can be traded. But instead of anyone showing up randomly, you require people to go through approved agents (brokers) who verify identities, handle paperwork, and ensure smooth transfers. Those agents charge a small fee for their service—that's exactly what brokerages do.

6. What Is a Share Price? (The "Auction" Logic)

Now that you understand how shares get to the stock exchange through an IPO, let's talk about what determines the price after that initial listing.

The Starting Point: Initial Listing Price

Remember from Section 3, the company and its advisors set an initial price during the IPO—let's say R100 per share. That's where the journey begins.

On the first day of trading, shares might open at R100. But within minutes, hours, or days, that price starts changing.

Why?

Because from the moment shares are publicly traded, the market determines the price—not the company.

Supply and Demand Drive the Price

The share price is what the market (all the buyers and sellers) is willing to pay for your portion of the business right now.

Crucial Point: The company does not set this price after the IPO. We do.

Here's how it works:

If more people want to buy than sell → Price goes UP

If more people want to sell than buy → Price goes DOWN

The Stokvel Analogy

Imagine that popular Stokvel we talked about earlier, now with 100 membership positions. After the IPO, 30 positions were sold at R20,000 each.

Word spreads that this Stokvel is extremely well-managed, consistent, and profitable. Everyone wants in. But all 30 positions are filled, and no one wants to leave.

Then one member gets a job overseas and decides to sell their position. Suddenly, three people want to buy it:

Person A offers R22,000

Person B offers R24,000

Person C offers R25,000

Person C wins. The "share price" of a Stokvel membership just went from R20,000 (the initial price) to R25,000—a R5,000 premium.

That premium is the share price going up because demand is high.

Why Prices Move Even When Nothing Changes

This is the fascinating (and sometimes frustrating) part of the stock market.

A company's share price can rise or fall even when nothing inside the company has changed.

Why?

Market sentiment: People feel optimistic or pessimistic about the economy

News and rumors: A competitor launches a new product; investors panic

Global events: Interest rates rise; investors shift money around

Quarterly results: The company reports profits higher or lower than expected

All of these factors influence demand—how many people want to buy vs. sell at any given moment.

The Auction Logic

Think of the stock exchange like a continuous auction:

Every second, buyers are placing "bids" (what they're willing to pay)

Sellers are placing "asks" (what they want to receive)

When a buyer's bid matches a seller's ask, a trade happens

That trade sets the current share price

If many buyers are bidding aggressively and few are selling, prices climb. If many are trying to sell and few want to buy, prices fall.

This is why share prices move constantly throughout the trading day.

7. Understanding Your "Return": The Cow Example

Many people ask: "How do I know if my investment is actually making money?"

In the city, they call this ROI (Return on Investment). In our communities, we have always understood this through livestock.

Imagine you bought a cow for R10,000 ten years ago.

Capital Growth: Today, because of inflation and demand, that same cow is worth R18,000.

The "Bonus": Over those ten years, your cow had two calves, worth R15,000 each.

Total Value: You now have R48,000 worth of cattle from your original R10,000.

That jump from R10,000 to R48,000 is your Return.

In a company, the calves are like Dividends—extra cash the company pays you just for being an owner. You can sell the "calves" for cash, or keep them to grow your herd even larger.

8. Opportunity Cost: The Money You "Don't See"

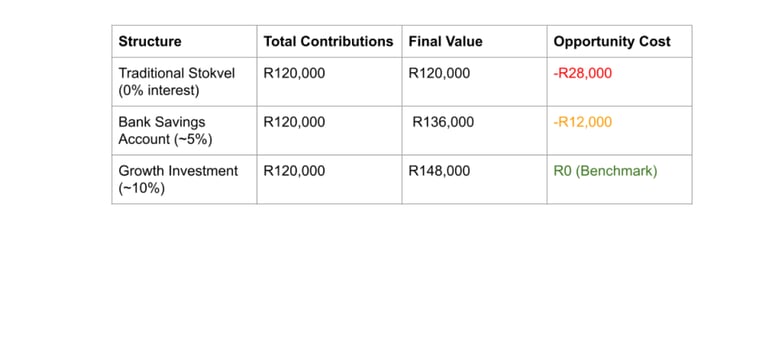

As you set your 2026 goals, remember: sticking to traditional cash-rotation Stokvels because they feel "safe" has a hidden cost called Opportunity Cost.

Look at what happens to R2,000 monthly contributions over 5 years:

9. Managing Risk: The "Stolen Cow" Strategy

Every investment has risk. In the village, your cow could be stolen. In a Stokvel, a member might fail to pay.

We manage this through Diversification.

Instead of putting all your money into one cow, you might start with goats. If one is stolen, you still have the others. In the stock market, you don't put all your money into one company. You spread it out (often using an ETF). If one business has a bad year, the others keep you safe.

10. The Power of Time: The Magic Ingredient

A Stokvel works because of the long-term commitment of its members. Investing is the same.

Short-term: Prices jump around. It looks like a gamble.

Long-term (5-10+ years): This is where the "magic" happens. Just like waiting for a calf to grow into a cow, wealth takes time to mature.

Final Thought: This Is How Wealth Is Built

Wealth is not built overnight.

It is built through:

Understanding value

Reducing opportunity cost

Giving your money time to grow

Stokvels taught us the discipline. Stokvel: Taking Our Strength to the Next Level

Formal investing gives us the structure.

This is how we move from simply saving for December to building a legacy for the next generation.

If this article changed how you think about money, the next step is understanding how to start.

Read our Beginner's Guide to Investing in South Africa

Bucks Insights

Your guide to practical finance and investing.

Tips

Investing

info@bucksinsights.com

083-577-6145

© 2025. All rights reserved.